The great Canadian climate delusion

Thomas Homer-Dixon and Yonatan Strauch

Globe and Mail

Is Canada going to be the first country to break apart over the issue of climate change? That may seem like a hyperbolic question. But the fissures in our federation over climate and energy policy are now extraordinarily deep, and there’s little sign that they’ll close soon. The federal Liberal decision to buy the Trans Mountain pipeline project will likely just widen them. Worse, some provincial politicians – especially United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney in Alberta – are now exploiting these fissures for political gain.

It’s not entirely about climate change, of course. Many people in British Columbia oppose the Trans Mountain pipeline because of the risk of ruptures along the pipeline’s route or of bitumen spills from tankers in coastal waters. Many Indigenous peoples don’t want the pipeline crossing their lands. But most opponents also find the project’s implications for global warming to be a deal breaker in and of itself.

For these opponents, further massive investment in the extraction and export of some of the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel on Earth is nonsensical – idiotic, even. In a dangerously warming world, we should be investing in a clean-energy future, not entrenching Canada more deeply in the economic past.

Continued investment in the oil sands generally, and in the Trans Mountain pipeline specifically, means Canada is doubling down on a no-win bet. We’re betting that the world will fail to meet the reduction targets in the Paris Climate Agreement, thus needing more and more oil, including our expensive and polluting bitumen. We’re betting, in other words, on climate disaster. If, however, the world finally gets its act together and significantly cuts emissions, then Canada will lose much of its investment in the oil sands and the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, because the first oil to be cut will be higher-cost oil such as ours.

Heads or tails, we lose. That’s the idiocy of it. We can’t have our lucrative oil sands profits and a safe climate, too.

This isn’t just rhetoric. Canada has no plan to meet its 2030 Paris Agreement emission targets, because it’s virtually impossible to do so if the oil sands’ output rises to Alberta’s cap of 100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year. Under the agreement, the global oil market won’t have room for our oil, either. Scenarios to limit warming to 2 degrees, the Paris Agreement’s bottom-line target, clearly show that oil demand must decline.

Even the conservative International Energy Agency’s 450 scenario (limiting the atmosphere’s greenhouse gas concentration to 450 parts per million, consistent with 2 degrees), which includes implausible carbon-capture and negative-emissions assumptions, shows demand peaking in the coming decade and then declining in subsequent decades. In a world limited to a 2-degree rise, the oil sands producers will lose customers first, even if OPEC market share declines. And tens of billions in unfunded oil sands cleanup costs will greatly compound the economic damage within Canada.

To those who think an oil-rich Canada can be a prosperous winner in a world that exceeds the Paris emission targets, it’s time to think again.

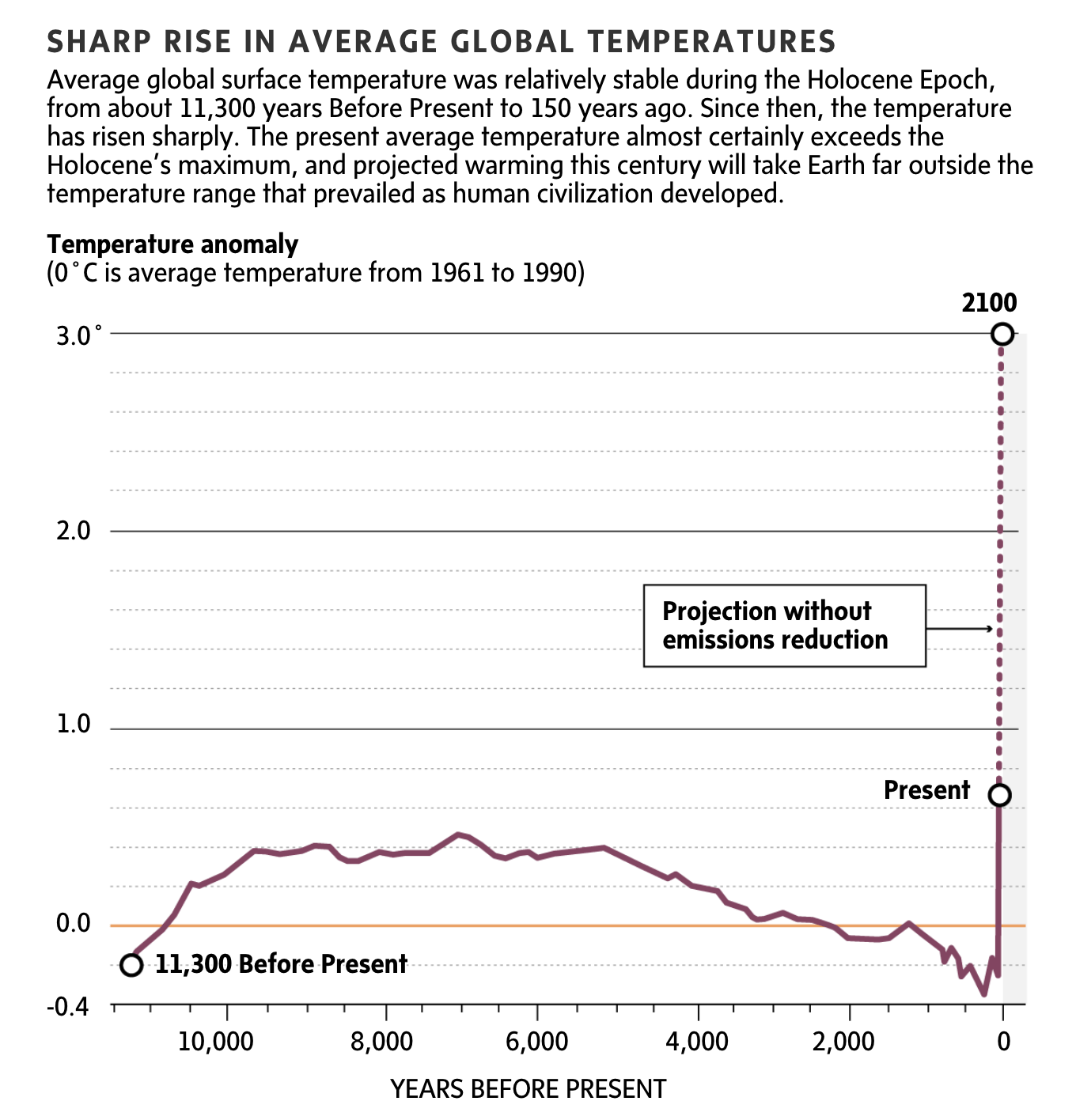

Recent, thoroughly peer-reviewed research shows that Earth’s average surface temperature has already risen slightly above the previous maximum during any time going back to the last ice age, about 12,000 years ago – which marked the beginning of the Holocene epoch (see the chart below). The world will likely see 2 to 3 degrees total warming before today’s children reach old age, if emissions aren’t sharply cut.

Folks who doubt mainstream climate science quibble about whether today’s temperature has exceeded the previous maximum. But that issue is a red herring. Here’s the really critical point that often gets overlooked: the projected change through the remainder of this century will push Earth’s average temperature up much further, vaulting it far outside its range over the past 2,000 years, a time during which humanity laid down the infrastructure of modern civilization – its agricultural zones, water-distribution networks, roads, ports, major cities and the like.

Canadian politicians and commentators often say, when confronted with such projections, that we’re simply going to have to adjust to the “new normal” of a climate-changed world – a world of more frequent and ferocious storms, floods, heat waves, droughts and forest fires. But there’s no normal any more, new or otherwise. We’ve already jumped from an equilibrium climate – the benign and largely stable climate that allowed our species to propagate and prosper over thousands of years – to a climate regime that’s constantly on the move, with temperatures shooting inexorably upward.

The German climatologist and oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf puts it bluntly: “We are catapulting ourselves way out of the Holocene.” If humanity stays on its current climate trajectory, he goes on, “we will not recognize our Earth by the end of this century.”

That’s the lens through which many of the pipeline’s most adamant opponents see the issue. To them, adaptation measures such as better flood protection or a little economic tinkering at the edges, such as a modest carbon tax, don’t remotely cut it. We face an implacable imperative: Humanity either undertakes fast and deep cuts in its carbon emissions or, some time later this century, civilization starts to unravel. This imperative has a moral component, too: Canadians should do their part to cut emissions, even if some countries aren’t currently pulling their weight. Otherwise, we’re simply free-riders, and that’s not who we are, or should be, as a country.

Canada should be doing what it can to help the world rapidly decarbonize, rather than hope its pipeline investments are protected from an energy transition gaining steam. Consider that, in just the past three years, China has deployed enough electric buses to displace nearly a quarter-million barrels of oil a day. The country has also mandated that auto makers sell 10 per cent electrics and hybrids next year and is developing a timetable to end production and sale of all oil-powered vehicles. Various European states have announced they will ban the sale of gasoline- and diesel-fuel vehicles, mostly between 2030 and 2040.

In Canada, in contrast, the Trans Mountain project and the commitment to the oil sands are contorting our politics and encouraging our leaders to use double-speak and cynicism to hide the terrible nature of our gamble. The federal government asks Parliament to ensure that all Canadian laws are harmonized with the United Nations declaration on Indigenous rights, which calls for “prior consent” just as it violates that principle by rushing pipeline consultations and approval. It commits to a world-class cleanup on the West Coast before the dangers of bitumen spills are fully understood. And it calls on businesses to disclose climate risk, but then hedges on heeding its own advice in the case of Trans Mountain.

We’ve already put a lot of precious chips down on this climate-disaster bet. We’ve given up, or seem prepared to give up, the environmental health of the waters and lands of Northern Alberta, reconciliation with many B.C. First Nations and genuine democratic practice in oil-infrastructure approval processes. More fundamentally, we’ve given up being honest with ourselves. We’re increasingly living in a delusional fantasy land in which our oil sands policies make environmental and economic sense.

As the planet warms, and as the world’s energy transition accelerates, the gamble at the heart of Canadian oil sands policy will only become harder to sustain. The more some of us try to hide that reality with double-speak and wilful self-delusion, the more the fissures in our federation will deepen, because others will call out the lies. So, the path we’re on – the path we took another huge step down this past week, courtesy of the federal Liberals – only leads to a fractured country. It’s our choice whether to keep going.

Yonatan Strauch is a doctoral candidate in the school of environment, resources and sustainability at the University of Waterloo.

Photo Illustration: Bryan Gee

Topics

Climate Change

Energy

Environmental Stress and Conflict