ACADEMIC

project on environmental scarcities, state capacity, & civil violence

KEY FINDINGS

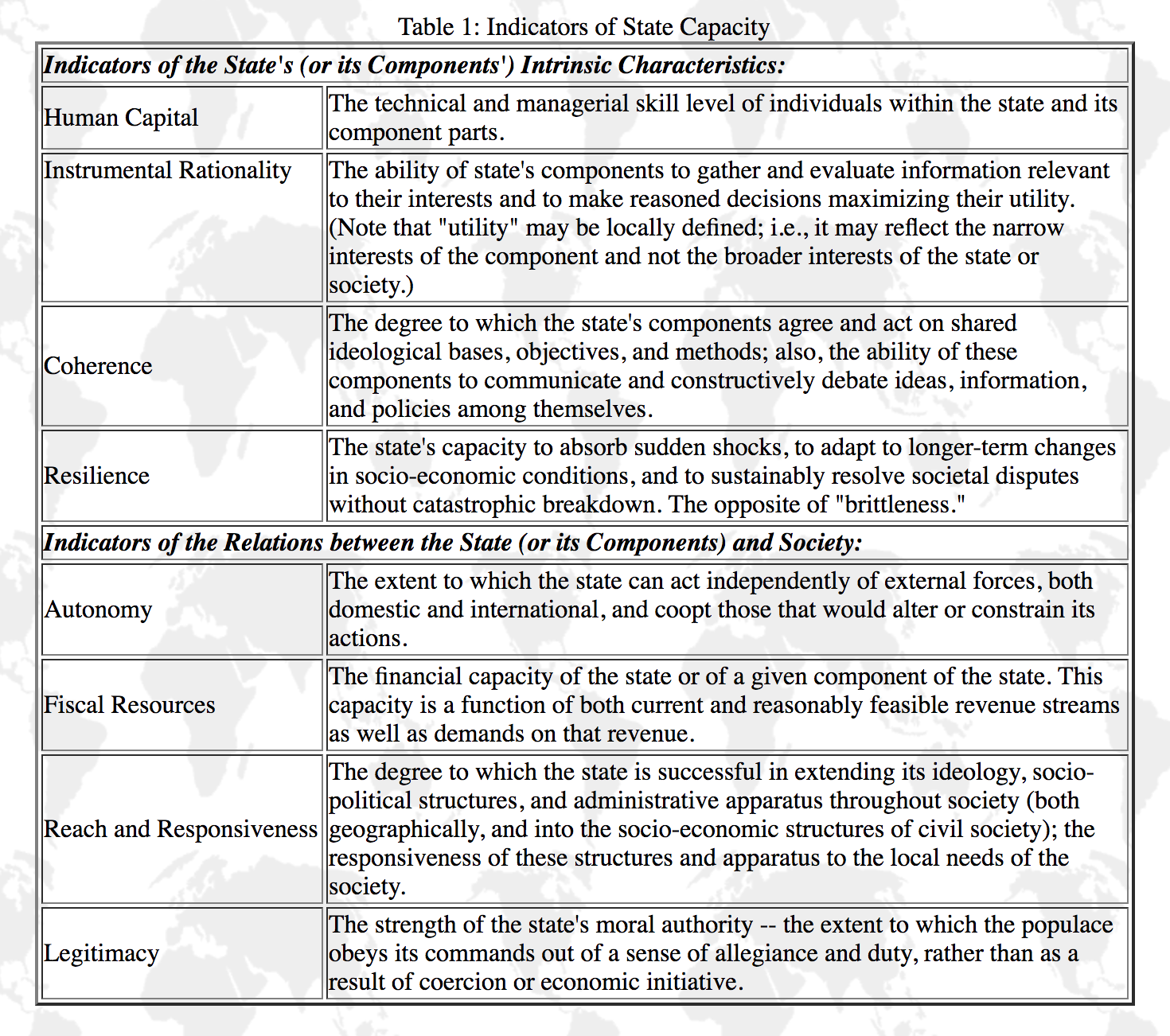

Project researchers and advisors, totalling about 50 experts in five countries, developed a detailed set of conceptual tools for thinking about environmental scarcity and state capacity. Environmental scarcity has three sources: reduced resource supply (from degradation or depletion), increased resource demand (from larger populations or higher per capita consumption), and skewed resource distribution. State capacity is a function of variables such as the state’s fiscal resources, political autonomy, legitimacy, internal coherence, and responsiveness (see Table 1 below).

This set of conceptual tools has allowed our researchers to identify links between rising environmental scarcity and declining state capacity. They have found four separate and often simultaneous effects:

- Environmental scarcities increase financial and political demands on the state. In addition, analysis of diverse cases — including those of South Africa, Pakistan, and the Philippines — shows that environmental scarcities expand marginal groups that need help from government by constraining rural economic development and by encouraging people to move into cities where they demand food, shelter, transport, energy, and jobs. In response, governments come under pressure to introduce subsidies of urban services; these subsidies drain revenues, distort prices, and cause misallocations of capital.

- Resource scarcities affect the state via their effects on elites. On one hand, scarcities can threaten the incomes of elites that depend on resource extraction. These elites often compete among themselves for shrinking resource rents; they may turn to the state for compensation, or they may act to block institutional reforms that would distribute more fairly the costs of rising scarcity. Scarcities can also aggravate competition among political elites that derive their power from rival political institutions. The management of such conflicts requires immense amounts of state attention, time, and money.On the other hand, environmental scarcities generate opportunities for powerful coalitions of elite members to capture windfall wealth. Scarcities can boost the economic power of small elite groups. As they become more powerful, these groups are increasingly able to ignore state dictates, shirk taxes on their greater wealth, and penetrate the state to make it do their bidding. In particular, they often lobby to change the property rights and other laws governing the use of scarce resources such as water, land, and forests. These groups have a great incentive to pursue such change: the state is usually able to generate large economic rents by expanding the range of permissible uses of resources and by granting monopolistic access to resources. In many societies, these rent-seeking elite groups influence the state through bribery, kickbacks, and other forms of corruption.

- Such predatory behavior by elites often evokes defensive reactions by weaker groups that directly depend on the resources in question. The struggle for resource control between powerful and weak groups, and among weak groups themselves, worsens social segmentation, which in turn debilitates civil society and erodes the trust-building processes that civil society promotes. The loss of trust, of information flows from society to the state, and of private implementation of state policies reduces the reach and responsiveness of the state at the local level. The state’s failure to meet local needs then depresses its legitimacy.

- If resource scarcity affects the economy’s general productivity, tax revenues to local and national governments can decline. Such a revenue decline hurts elites that benefit from state largesse and reduces the state’s capacity to meet the increased demands arising from environmental scarcity.

We see, therefore, that environmental scarcity can affect a number of the variables measuring state capacity. It can directly constrain a state’s fiscal resources, and by encouraging predatory behavior by elites, it can reduce state autonomy. Rivalry among political elites reduces coherence, and competition among groups over resources weakens civil society. The conjunction of these four changes, in turn, hinders state responsiveness by reducing its ability to supply social ingenuity in the form of efficient markets, clear property rights, and an effective judicial and police system. Environmental scarcity can also boost financial and political demands on the state and increase grievances of marginal groups. A widening gap between rising demands and state performance, in turn, erodes state legitimacy, further aggravates conflicts among elites, and sharpens disputes between the elites and the masses. As the state weakens, the social balance of power can shift in favor of groups challenging state authority.